But even through the lime-green optics of her night-vision goggles, Roselli was able to see that those iconic marshlands — once the largest wetlands in the Middle East — were now nearly gone.

“It was desert as far as the eye could see,” says Roselli, who is enrolled in the F&ES joint degree program with Vermont Law School. “I knew from research that it used to be there. But I could tell it no longer was.”

At the time, Roselli wondered how such an environmental catastrophe could happen in such an important ecosystem, which some believe inspired the biblical Garden of Eden. She also wanted to know how the ecological degradation was affecting Iraqi communities, especially the indigenous Marsh Arabs who have lived in the marshes for 5,000 years.

And she wanted to learn how such conflict-based environmental disasters might one day be repaired — or prevented altogether.

This curiosity eventually led Roselli to F&ES. “I came here for one reason and one reason only,” she says. Since arriving, she has tailored her coursework around the study of water issues, the intersection of water management and human rights, and the restoration of war-torn environments.

And throughout her studies, her focus has returned to Iraq.

“I’m particularly interested in the water diplomacy between Iraq and its upstream states,” she said. “Particularly Turkey, since Turkey has the most control over Iraq’s water at this point, which will obviously have a downstream effect on the marshes.”

In the summer of 2013,

Roselli returned to Iraq, albeit under very different circumstances. Although she is still a member of the Vermont Army National Guard, she wasn’t surrounded by a “large entourage” on this trip, she says, and wasn’t wearing a soldier’s uniform. Instead, she was working with the group

Nature Iraq, an Iraqi NGO aiming to restore and preserve the country’s natural heritage and support the adoption of more sustainable environmental policies.

During her travels, she typically did not mention that she’d previously been in Iraq as a U.S. Army officer. But she was quite surprised at the appreciation she received as an American. (Although, she concedes, the reaction might have been different if she wasn’t visiting primarily Kurdish regions.)

In the communities she visited, she found a sense of optimism that the country was ready to move forward after years of war. “For the first time in a very long time people have opportunities to do all these things they’ve wanted to do,” she said. “Culturally, they’re in this incredible bounce-back mode where everything is about progress, everything is about the economy.”

For most people, however, water issues are still not a priority. Most of the people she met didn't seem to realize how much their future water supplies depend on the policies of Turkey, or how water management in Iraqi Kurdistan will affect water availability for the rest of Iraq, including the region in and around Baghdad. Likewise, there is little recognition that Baghdad’s history of water mismanagement and aging infrastructure has left barely a trickle of water to sustain Iraq's southern marshes and their surrounding communities downstream.

Fortunately, when Roselli talked with people involved in environmental issues, she sensed a growing urgency to tackle these risks through more sustainable management strategies, additional green spaces, and education initiatives.

“And they are really driven,” she said. “I think if enough key leaders are really driven, over time things will change.”

When she was in Iraq the first time, as a soldier, Roselli spent nearly all of her time on a barren, tree-less, military base. The only place that even resembled home — the only place where “green stuff” grew — was a water-bottling plant that had a reservoir with pockets of reeds that attracted the few birds that still lived nearby.

“Almost every morning, after working the night shift, I would go there either to run around the track or to just sit there with my camera and take pictures,” she remembers.

For Roselli, who had always been an amateur birder, this pocket of the natural world was a critical source of mental escape. But it was also a grim reminder. Those last remaining birds, she thought, were a bio-indicator that these wetlands, which have been so critical to humans and wildlife for thousands of years, were vanishing.

And if the system is allowed to disappear completely, she thought, the loss of natural and economic services — from food and drinking water to an irreplaceable cultural heritage for indigenous peoples — would be staggering.

“I thought of how important these places must be to the Iraqi people because of how important that little spot of water was to me,” she said. “At the most basic level, these wetlands represent Iraq’s cultural and environmental history.”

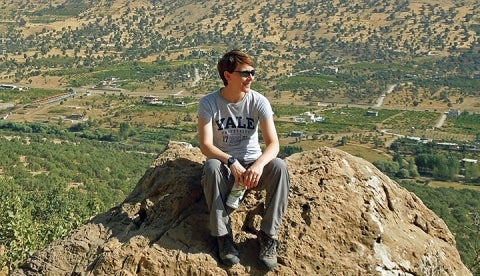

Carina Roselli in Kurdistan during the summer of 2013.

Carina Roselli in Kurdistan during the summer of 2013.

<p class="p1"> Roselli, top, at the controls of a Chinook CH-47 during her deployment in Iraq. Below, a night-vision-goggle view of a village in southern Iraq.</p>

<p class="p1"> Roselli, top, at the controls of a Chinook CH-47 during her deployment in Iraq. Below, a night-vision-goggle view of a village in southern Iraq.</p>

A Pied Kingfisher hides in the reeds at a water bottling plant at Combat Operating Base Adder, where Roselli lived during her Iraq deployment.

A Pied Kingfisher hides in the reeds at a water bottling plant at Combat Operating Base Adder, where Roselli lived during her Iraq deployment.