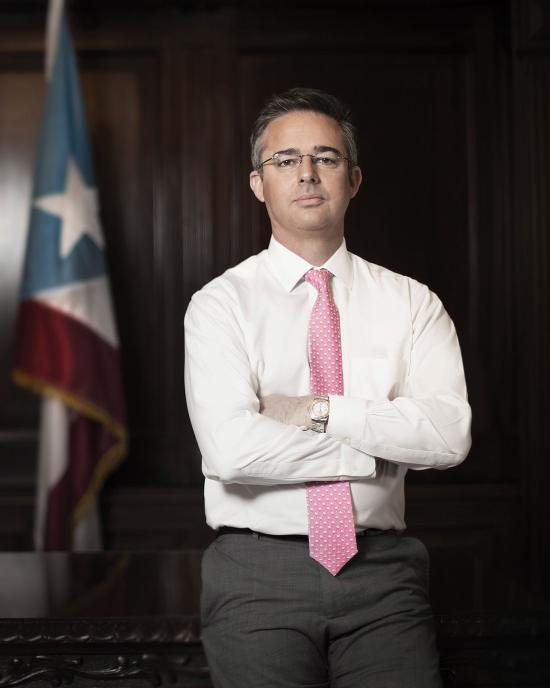

A camera placed by Siria Gámez in the cloud forest section of El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve, known as “Venado,” captures an image of a tree porcupine waiting for her offspring that are climbing behind her.

Examining Vertical Spaces: What’s Living in the Canopy?

Up in the trees in Mexico’s El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve, high above the forest understory, is a microcosm of biodiversity — tayras, coatis, margays, and kinkajous. To gain a better understanding of these treetop species, YSE PhD student Siria Gámez climbs 80 feet straight up into the canopy to set up camera traps that allow her to observe the wildlife firsthand. Reaching such heights in remote areas can involve swinging from one limb to another, finding oneself in the middle of screeching monkeys and carrying as much as 16 pounds of equipment.

For her doctoral research, Gámez is testing several different hypotheses about the factors driving the levels of activity of animals in the canopy, including pressure — or lack of pressure — from jaguars and pumas, whose populations are facing their own challenges.

“I’ve had an interest in carnivores for a long time,” says Gámez, a student in YSE’s Applied Wildlife Ecology Lab (AWE) directed by Knobloch Family Associate Professor of Wildlife and Land Conservation Nyeema C. Harris. “For me, it’s their beauty and their significance as the apex species. They have profound impacts on what a community looks like and are important cultural icons.”

Much research has been done on the ground on apex predators, Gámez notes, but not in the three-dimensional spaces that include the tops of tropical forests where predators may be driving prey.

“We haven’t, for the most part, been able to answer the question, what is up there and why? This research is groundbreaking in that it’s one of the very first studies that pairs canopy and ground cameras to target carnivores,” says Gámez, who completed a strenuous training course in Panama last year in order to be able to scale the trees safely.

One of her scariest moments was when she needed to switch her ropes to another limb so she could get a better angle on a spot to install her camera. The tree was on a hilltop with a steep drop into a canyon.

“To change ropes, you have to set up the second rope system and then undo the first. In this case, it was just extra unnerving because I was over this valley, and I was just swinging. Every instinct I had told me, just hang on, do not let go of this first rope,” she remembers.

“I’ve had an interest in carnivores for a long time. For me, it’s their beauty and their significance as the apex species. They have profound impacts on what a community looks like and are important cultural icons.”

Data from her camera traps are already coming in, and she is finding that there is reduced animal activity in the canopy of trees near agricultural sites in El Triunfo. She is also examining mosquito DNA from traps she sets in the canopy to research connections to zoonotic illnesses.

Gámez hopes the data she collects will lead to a better understanding of the spatial ecology of arboreal mammals — knowledge that is crucial for their conservation.

“It’s important to use the data that we’re collecting to improve the outcomes for animals but also for people,” she says. “What sort of management activities can we come up with so folks still have their livelihoods while also reducing the impact on arboreal animals?”

Harris has been impressed with Gámez’s consistent dedication to her research in El Triunfo and says it fills a critical knowledge gap.

“Siria’s investment in building this project is truly impressive, from the tree-climbing class to the scoping trip to taking classes to learn the local Nahuatl language. Her work will yield new insights into carnivore space use in a three-dimensional community context amid considerations of land use,” Harris says.

As her work progresses, Gámez has gained a new appreciation for vertical spaces and their inhabitants.

“Once you’re up in the canopy, it’s absolutely gorgeous. It’s just otherworldly,” she says. “And the most exciting possibility for me to discover is whether the canopy might be a nice refuge where animals can shift up and escape a little bit of the pressures on the ground.”