In 2021, Yale Program on Climate Change Communication Director Anthony Leiserowitz ranked No. 2 on the Reuters Hot List of scientists whose work is having the biggest impact on the climate change debate globally. Christopher Capozziello

The Climate of Climate Change Is Shifting

While research by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication at YSE shows a fundamental shift toward climate change action in the U.S., founder and director Anthony Leiserowitz says people everywhere need to better understand what the solutions are, as even those most convinced global warming is happening and supportive of climate policies often don’t know what to do.

It’s hard to imagine a research lab involved in more far-reaching or varied projects than the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. The group conducts nationally representative surveys and message experiments, identifies key audiences, and models and maps public opinion on climate change at global, national, state, and local scales. But YPCCC, as founder and director Anthony Leiserowitz notes, is not a typical research lab. In addition to conducting research on climate change beliefs, attitudes, and behavior around the world, YPCCC partners with governments, media organizations, companies, and civil society organizations to build public and political will for climate solutions. The group is currently working with the Irish government on a national strategy to engage its population in climate change solutions. At the same time, they are working with name-brand companies designing new products and services to help people implement climate solutions in their lives and hundreds of advocacy organizations pushing for climate action. They also publish “Yale Climate Connections,” an online climate news service, podcast, and daily radio program available on more than 700 frequencies nationwide. In a wide-ranging conversation, Leiserowitz talks about a recent shift in Americans’ attitudes on climate change, global trends, and a communications challenge that companies haven’t mastered yet.

To many people, not just at YSE and Yale but across the global climate community, your name is synonymous with research on climate change communication, but not everyone knows how you got your start. What’s the origin story?

I went to college at Michigan State, where I studied U.S., Soviet, and Chinese nuclear policy. I thought I had a whole career ahead of me trying to keep the world from blowing itself up. Then, six months before I graduated, the Berlin Wall came down. My international relations degree turned into a history degree overnight. I followed a friend to Aspen, Colorado, with the intention of earning some money so I could travel around the world. But I ended up instead getting one of the first staff positions at the Aspen Global Change Institute.

I spent four years there working with many of the world’s top climate scientists, and it changed my life. It’s why I do what I do today. It was 1990, and at the time most people were barely conscious of climate change. Yet, I was learning just how dire the problem already was. The critical thing, however, is that by the end I was getting a bit frustrated with the primary focus on the natural sciences — not with the people. The scientists themselves were fantastic, but I kept coming back to, “Okay, so we’ve got this global problem, climate change, but why? What is it about human beings that creates these global problems in the first place, and then how do we get human beings to work together to solve them?” Those questions led me back to graduate school, where I did my PhD at the University of Oregon in Environmental Science, Studies, and Policy, with a focus on risk perception, decision-making, and communication with one of the pioneers of the field, psychologist Paul Slovic.

All the important decisions of life: Where do I go to school? What career should I choose? Should I take this job? Marry this person? All of these are examples of decisions made under conditions of risk and uncertainty. Climate change is a premier example of this because the potential risks are so severe and there's so much uncertainty about the future.

Does the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, as well as some of the policies that have been enacted at the state level, signify a shift in Americans’ attitudes about climate change?

Overall, we still lack sufficient public and political will for climate action. We are not lacking a supply of solutions. We have lots of great solutions. We have great technologies. We have products. We have business models. We have policies that are well known, tested, and sitting on the shelf. But we lack sufficient demand for those solutions, and that’s what we call public and political will.

Now, within that frame, we have measured some vitally important shifts in public will in the U.S. that have led to policies like the IRA. While we study public support for policies like the IRA, I’m ultimately more interested in recent shifts in the underlying social, cultural, and political climate of climate change; that’s the really important thing.

Anthony Leiserowitz, YSE senior research scientist and director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, gives a public lecture, “Climate Change in the American Mind,” at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln on March 10, 2015.

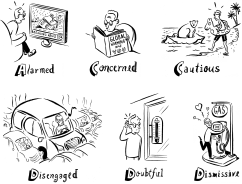

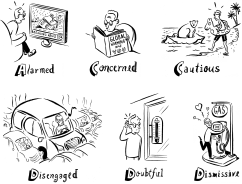

One of the major shifts we’ve observed relates to “Global Warming’s Six Americas.” In 2008, we and our partners at George Mason University identified six different audiences within the United States who each respond to the issue of global warming in different ways. You can think of them along a spectrum. At one end are the Alarmed, those who are fully convinced it’s happening, human-caused, serious, and urgent. They strongly support action. At the other end are the Dismissive, those who are firmly convinced it’s not happening, not human-caused, and not a serious problem. Many are conspiracy theorists. Then, in between those, you’ve got four other groups: the Concerned, the Cautious, the Disengaged, and the Doubtful.

In many ways the two groups on the ends — the ones who either raise their voices and say we want action or raise their voices and say we don’t want action — are the most important from a political standpoint. Six years ago, the Alarmed and the Dismissive were each about 11% or 12% of the U.S. population. But since then the Alarmed have grown dramatically. As of last year, they are 26%, while the Dismissive are still about 11%. Whereas six years ago, there was one Alarmed for every one Dismissive, now there are more than two Alarmed for every one Dismissive in the country. That reflects a fundamental shift in the social, cultural, and political climate of climate change toward action.

YPCCC has recently studied attitudes about climate change in developing countries. What have you found?

We recently conducted a global study in 110 countries and territories in partnership with Data for Good at Meta. We found that about 2 billion people, especially in the developing world, say they know little to nothing about climate change. Many of them have never even heard the term. Despite all the science, global conferences, and media coverage, you still have roughly a fifth of humanity who know little to nothing about climate change. The world still needs to raise basic awareness, especially among the most vulnerable.

“But not knowing about climate change doesn’t mean people aren’t keenly aware of changes in their local climates. They are.”

But not knowing about climate change doesn’t mean people aren’t keenly aware of changes in their local climates. They are. Most of these people know that temperatures are changing. They know that rainfall patterns and growing seasons are changing. They know that the frequency and severity of droughts and floods are changing. They just don’t know that these are often caused by climate change. And they don’t understand that continued global warming is often going to make these things worse.

But the good news is that it doesn’t take a lot. When we just give these respondents a one-sentence description of what climate change is and how it affects weather patterns, we find that immediately over eight out of 10 people around the world say, “Yes, that’s happening. Yes, I’m worried about it. Yes, I support my government taking action.”

I’d also add that people everywhere need to better understand what the solutions are. Even the Alarmed often don’t know what to do. What can we do as individuals? What can we do as communities? What can we do as a nation or the world to actually solve this problem?

Even when climate action seemed stalled at the government level, at least in the U.S., there did appear to be some forward movement among many in the private sector. Does that align with your findings?

First, there are some companies who early recognized the need to act on climate change. But, yes, when I say public will, that doesn’t just mean pressure on politicians to act, it also includes putting pressure on companies to act. We’ve seen growing intensity as well as broad-based support for companies taking action. When we ask Americans who they think is most responsible for acting to address climate change, they identify corporations at the very top, above government. In fact, over half of consumers say they are willing to reward or punish companies for their actions, or failure to act, but we know that many are not currently doing so. So then we ask, “What are the barriers? Is it that the products cost too much? Is it that they’re lower quality or not available?” What we consistently find is that it’s one barrier more than any other preventing people from rewarding or punishing companies. They simply don’t know which companies to reward or punish.

There are, of course, significant risks of greenwashing, which we’re seeing out there in the media landscape. But there’s a very strong interest and motivation by millions of U.S. consumers to vote with their dollars on a daily basis. But nobody has yet figured out how, at scale, to inform these consumers what’s a good product, what's a bad product, what’s a good service, and what's a bad service when it comes to the climate. In other words, it’s a communications challenge — and opportunity!