Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

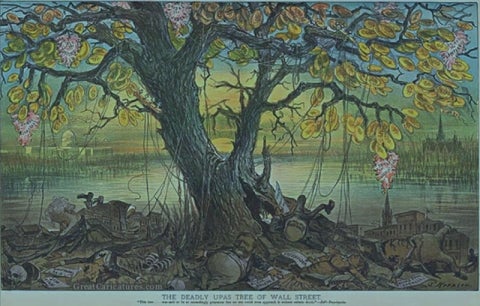

In this 1882 cartoon, the poison tree is a metaphor for Wall Street.

In this 1882 cartoon, the poison tree is a metaphor for Wall Street.

When the first English edition of The Ambonese Herbal, a 17th century masterwork in the study of botany, was published three years ago, the description of one intriguing plant caught Michael R. Dove’s attention.

The plant was called “the poison tree from Macassar.” And as Georgius Rumphius, the German naturalist who produced the monumental Herbal, wrote, he “had never heard of a more horrible or more villainous poison from plants.” A tree in the mulberry and fig family, it was the source of a deadly poison that native tribesmen would fire at Dutch soldiers through blow-pipe darts during their explorations of the West Indies.

The description of the tree is colorful and exaggerated, says Dove, a professor of anthropology and social ecology at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. Indeed, Dove says, it constitutes one part of the Herbal in which “the observations of one of the greatest naturalists of his time seem most suspect.”

In a new article published in the journal Allertonia, Dove asserts that Rumphius’s description of the so-called “poison tree” and a subsequent obsession with the plant in the western world — it was mentioned by Byron and Pushkin and was the subject of a 19th century play in London — reflect the important role of imagination and exaggeration in western perceptions of the East that continues to this day.

The plant was called “the poison tree from Macassar.” And as Georgius Rumphius, the German naturalist who produced the monumental Herbal, wrote, he “had never heard of a more horrible or more villainous poison from plants.” A tree in the mulberry and fig family, it was the source of a deadly poison that native tribesmen would fire at Dutch soldiers through blow-pipe darts during their explorations of the West Indies.

The description of the tree is colorful and exaggerated, says Dove, a professor of anthropology and social ecology at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. Indeed, Dove says, it constitutes one part of the Herbal in which “the observations of one of the greatest naturalists of his time seem most suspect.”

In a new article published in the journal Allertonia, Dove asserts that Rumphius’s description of the so-called “poison tree” and a subsequent obsession with the plant in the western world — it was mentioned by Byron and Pushkin and was the subject of a 19th century play in London — reflect the important role of imagination and exaggeration in western perceptions of the East that continues to this day.

You can almost draw a lineal line of descent from the weapons of mass destruction that did not exist in Iraq to the fabulous poison tree of the 17th century.

At the time, Dove writes, the Dutch were terrified of the tree largely because its poison was an unknown entity. And while its properties were fairly innocuous in comparison to the gunships used by the Dutch, the Europeans reacted by concocting fantastical explanations. In time, they would share stories that the toxicity of the tree was such that no living thing could survive within 20 miles of it, that it would knock birds out of the sky, and that local sultans sent condemned prisoners to harvest its poisonous sap.

Such myth-making, Dove says, represents the foundation of modern western views about the Eastern world.

“From a modern perspective, you see a tradition of Orientalizing a non-western secret, a non-western threat, that we don’t understand yet we need to understand,” he says. “You can almost draw a lineal line of descent from the weapons of mass destruction that did not exist in Iraq to the fabulous poison tree of the 17th century.”

This interpretation, Dove says, builds upon a theoretical framework established in Edward Said’s book, Orientalism, which argues that Western assumptions about the East (and the West) fueled cultural biases and misrepresentations that collectively can be called “orientalism.”

Such myth-making, Dove says, represents the foundation of modern western views about the Eastern world.

“From a modern perspective, you see a tradition of Orientalizing a non-western secret, a non-western threat, that we don’t understand yet we need to understand,” he says. “You can almost draw a lineal line of descent from the weapons of mass destruction that did not exist in Iraq to the fabulous poison tree of the 17th century.”

This interpretation, Dove says, builds upon a theoretical framework established in Edward Said’s book, Orientalism, which argues that Western assumptions about the East (and the West) fueled cultural biases and misrepresentations that collectively can be called “orientalism.”

The poison tree as a metaphor for alcohol in the 19th century.

The poison tree as a metaphor for alcohol in the 19th century.

You could say that from the 17th century to the present, there has been a sort of prepared receptivity to this story of natural resource wealth, the alien ‘other,’ and credulous belief in fabulous weapons,” Dove says.

In the Allertonia article, Dove notes that this phenomenon was not restricted to the westerners. The colonial relationship, he says, provoked imaginative interpretations of plants by the native populations, too. During the same era, he writes, some native populations came to see black pepper (Pipe nigrum L), one of the critical goods of the spice trade, as a source of evil. In some native states, rulers tried to abolish its trade, claiming that its “hot vapours” led to “malice all over the country.”

“This is one of the great values of Rumphius’s work,” Dove writes. “It illuminates the confluence of East and West in the production of knowledge in the early modern era, and it bears lessons for understanding the role of the imagination in perceptions of natural resource wealth, enemies, and the Orient to this day.”

Dove’s article appears in a special issue of Allertonia that honors the publication of The Ambonese Herbal by Yale University Press, and E.M. Beekman, the late author and professor of Germanic languages at the University of Massachusetts, who was instrumental in producing the new translation.

In the Allertonia article, Dove notes that this phenomenon was not restricted to the westerners. The colonial relationship, he says, provoked imaginative interpretations of plants by the native populations, too. During the same era, he writes, some native populations came to see black pepper (Pipe nigrum L), one of the critical goods of the spice trade, as a source of evil. In some native states, rulers tried to abolish its trade, claiming that its “hot vapours” led to “malice all over the country.”

“This is one of the great values of Rumphius’s work,” Dove writes. “It illuminates the confluence of East and West in the production of knowledge in the early modern era, and it bears lessons for understanding the role of the imagination in perceptions of natural resource wealth, enemies, and the Orient to this day.”

Dove’s article appears in a special issue of Allertonia that honors the publication of The Ambonese Herbal by Yale University Press, and E.M. Beekman, the late author and professor of Germanic languages at the University of Massachusetts, who was instrumental in producing the new translation.

– Kevin Dennehy kevin.dennehy@yale.edu 203 436-4842

Published

March 17, 2014