Connection, Growth and Change

Alumnus startup looks to reimagine the urban tree lifecycle with “reforestation hubs.”

Alumnus startup looks to reimagine the urban tree lifecycle with “reforestation hubs.”

When Ben Christensen ’20 MEM set out to establish a company that would reimagine the urban tree lifecycle — and help combat climate change in the process — he was inspired by the role of the plant tissue cambium, which supports the secondary growth of trunks, branches, stems, and roots to make a tree healthy and full.

Thus, Cambium Carbon was born.

“Cambium, within a tree, is about connection and growth,” says Christensen. “Those are two things we see our company being able to do. We want to connect the dots and facilitate growth across the system.”

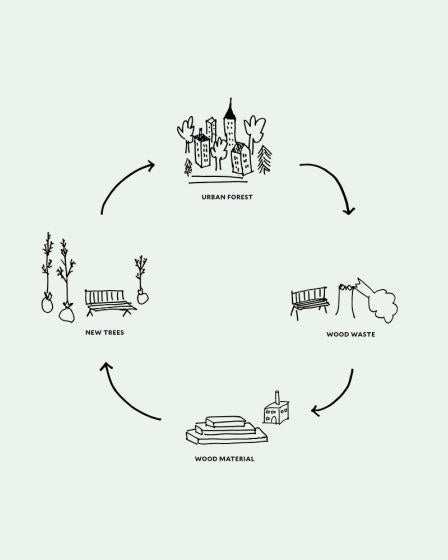

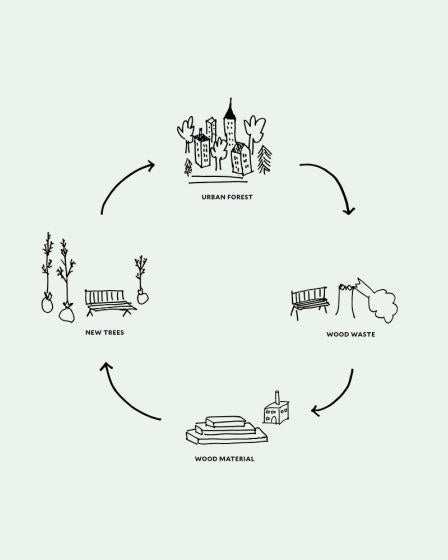

The company is aiming to build “reforestation hubs,” a first-of-its-kind private-public partnership that restores city forests across the U.S. The company is creating funds to plant trees in urban natural areas by valuing their benefits — like the raw wood material they provide and their ability to absorb carbon dioxide — to help turn the tide of urban forest loss. Today fallen trees are often chipped for low-grade application or hauled to a landfill at significant cost; Cambium Carbon is working to build systems for processing that wasted material into higher-quality wood products that can subsidize future tree-planting efforts.

Researchers say the supply is there. A 2019 report from the U.S. Forest Service estimates that annual urban woody biomass loss totals about 46 million tons of sellable wood with a potential value of more than $700 million. Cambium Carbon sees opportunity in the current inefficiency and aims to create a sustainable cycle by closing the resource loop, working with stakeholders at each step — from parks departments and arborists who manage urban trees to local millers and makers who craft wood products and on to established tree-planting programs.

One key to success will be understanding the needs of individual cities. Most cities in the U.S. have gaps in their urban forestry system — a city like Detroit has thousands of dead trees it’s unable to remove due to financial constraints, while a city like Honolulu suffers from a lack of space to dispose of wood waste. And if wood was provided to local millers and makers, very few have the resources to create a large-scale manufacturing operation, as most focus on small-scale, high-end products.

Identifying where each city’s gaps are, Christensen highlights, is critical.

“We’re not trying to steamroll in; there are too many similar programs that have failed because they didn’t have community buy-in,” he says. “We need to listen. We want to work with partners who understand their city inside and out. We want to be an external catalyst that can provide resources along the way to help them grow.”

Right now, Cambium Carbon is identifying municipalities across the country to form a cohort of pilot cities for initial analysis — a requirement of a substantial grant Cambium Carbon received from The Nature Conservancy earlier this year, in partnership with tree-planting nonprofit The Arbor Day Foundation. Marisa Repka ’20 MEM, Cambium Carbon’s city partnership lead, says they’ve received letters of interest from over 30 diverse cities, some of which have structures in place for organic waste processing and tree planting and some that are looking to establish stronger systems.

“We’ve even seen interest from small cities, which has us thinking about the potential for regional programs,” adds Repka. “We’re realizing this can work on a lot of different scales. It’s exciting.”

One city that has led the way in wood utilization is Baltimore, which has a dedicated wood waste recovery yard and has created a robust marketplace to sell wood products. Private entities, like Urban Wood Economy, supplement the city agencies and local stakeholders within Baltimore to strengthen the efforts.

Jeff Carroll, co-founder and principal at Urban Wood Economy, has worked with Cambium Carbon and sees them becoming a “significant player” in this space.

“They’re an implementor,” says Carroll. “They’re actually providing the services and the resources where there are pieces missing in the chain. And even though they’re newcomers, they’re leveraging established connections in the wood business.” Carroll envisions Cambium Carbon being able to work in varying capacities — from overseeing individual tasks such as sales and distribution or tree planting to developing and operating the entire process in cities most in need.

The goals are lofty for the fledgling startup, which Christensen conceived during an internship with the World Resources Institute in 2019, where he worked on federal carbon removal policy. Taking his recently developed modeling skills from YSE lecturer Daniel Gross’s ’92 BA, ’98 MBA/MEM class on renewable energy project finance, he developed a national model that prioritizes federal spending for natural climate solutions. Realizing the need for innovative financing and community impact, he started developing the “reforestation hubs” model that has become core to Cambium Carbon.

After bringing in his friend and classmate Repka, who had just completed a policy internship with Honolulu’s Office of Climate Change, Sustainability, and Resiliency, Christensen began seeking initial funding from individual investors to launch Cambium Carbon. The project then won funding from the Sobotka Seed Stage Venture Program and a Climate Change Innovation Seed Grant from the Yale Center for Business and the Environment, which positioned Cambium Carbon to earn critical support as a member of the fall 2019 Accelerator cohort of the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale.

To succeed, though, Cambium Carbon will have to become self-sustainable financially. Christensen and Repka — who were recently named to 2021 Forbes’ “30 Under 30” list for social impact — are confident the need is there, particularly at a time when budgets for trees and natural areas in cities are dwindling.

“It’s a hard time across the country,” Christensen says. “We’re here to solve real problems. We can help cities save money, reduce waste, create jobs, fight climate change — there’s a lot of exciting potential.”