Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

When Chris Williams began renovating Greeley Memorial Laboratory in 2009, he started from the ground up — literally — in the basement. “There was always a 2-inch pool of water there,” says Williams, the lead architect for the project. “In order to go in, you had to wear sandals because it was constantly flooding from groundwater.”

“The basement was basically a mini tidal plain,” echoes Jan Taschner, superintendent of facilities for the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). “There were two-by-fours on the ground for maintenance to walk on.”

“The original drainage system had become clogged with sand, which happens over time,” Williams explains. “So we dug up the floor and put in a new system to dry it out. And once we were able to dry that out, we were able to renovate the space.”

The original lobby of the Greeley Memorial Laboratory, during the early 1960s.

The original lobby of the Greeley Memorial Laboratory, during the early 1960s.

After nearly seven years, Greeley’s renovations are now complete. The renovations have served to both address issues of basic infrastructure and to upgrade the laboratory facilities. In addition to the Center for Green Chemistry, Greeley is home to offices and lab space for F&ES faculty members.

Nearly $12 million has been invested in Greeley. The funds have been made available primarily through carefully timed withdrawals from the School’s capital replacement charge account. This phasing has spread the financial impact over several years in order to accomplish the renovations while simultaneously allowing the School to develop a secure financial position for the future.

Greeley’s basement now holds new mechanical systems — including four energy-saving boilers — an elevator, and a state-of-the-art wet lab featuring cherry cabinets, epoxy countertops, and a free-floating grid that creates an implied ceiling plane for the Center for Green Chemistry & Green Engineering at Yale. Natural light illuminates the lab through new trapezoidal windows that Williams installed. “This basement space is completely above grade, next to this beautiful garden. Why wouldn’t you put windows in it?” Williams says. “It really helps increase the real estate value, and it lets the researchers know that there’s an outside.”

But installing a new drainage system — and other renovations such as venting air through the roof or installing new ductwork — in a mid-century building made almost entirely of huge precast concrete slabs is not as simple as it may appear.

The original reception desk, circa 1960.<br />

The original reception desk, circa 1960.<br />

“When you look at these buildings, it seems easy because everything’s out in the open,” Williams says. “But in reality, they’re probably one of the hardest types of buildings to restore because you don’t have places to conceal things. It’s just concrete. For example, a lot of the conduit for the lighting is embedded in the concrete. So it’s not very easy to change that, or to put new in.”

The building, named for William Buckhout Greeley 1904 M.F. ’27 M.A. Hon, was the first designed for Yale by architect Paul Rudolph, who served as the university’s Dean of the School of Architecture from 1958 to 1965. Rudolph, who also designed Yale’s Art & Architecture Building (now Rudolph Hall), is well-known for his modern, “Brutalist” aesthetic that favors heavy use of simple, precast concrete and open plan concepts. Among other projects, Rudolph also designed New Haven’s Temple Street Parking garage, Boston’s Government Center, and the main campus of the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute (now the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth).

Current Architecture School Dean Robert A.M. Stern describes Rudolph as one of the most respected architects of his generation, both in the United States and internationally. “He was a master of design,” Stern says. “A romantic figure who synthesized the spatial power of Frank Lloyd Wright and the love of heavy brutalized use of béton brut, which means exposed concrete — which is the origin of Brutalism.”

After drying out the basement, Williams’ team moved on to Greeley’s lobby, bringing back Rudolph’s open floor plan. Rudolph’s design originally included a reception desk, but Williams scrapped the desk in favor of a common meeting space. He added custom-designed benches and Eero Saarinen chairs to create a collective gathering space where students and faculty meet to discuss research projects, relax, and host events. Lighting illuminates ductwork behind columns, and puts it on display. “It’s like it says, ‘Yeah, there’s a lot of mechanical stuff serving these labs,’” Williams says. “It’s actually one of my favorite parts of the design because the service and structure of the building are all kept out in the open, all exposed.” The open space features Rudolph’s distinctive Y-shaped concrete columns that support a concrete ceiling punctuated with skylights. Some believe Rudolph intended the Y’s to look like trees reaching towards the canopy above.

Partitioned offices in lobby removed for current renovation

Partitioned offices in lobby removed for current renovation

F&ES Prof. Graeme Berlyn, who joined the faculty in 1960, was one of Greeley’s earliest inhabitants. Initially, the building housed the School’s wood science program. Berlyn says Rudolph worked with the faculty to design a state-of-the-art lab that ended up attracting other researchers from across the university such as engineers and medical students. “We had a very well-controlled plant growth room where we could vary temperature and light, and the big plant-growth rooms were gas-sealed so we could do carbon dioxide enrichment experiments,” Berlyn says. “This was a new type of design. [Rudolph] envisioned it as just a single floor laboratory space, and so that’s why he didn’t do anything with the basement. The bad part about what happened after that is that everything was done piecemeal. There was no architect involved and so there was no overall planning of these things.”

By the time Dean Peter Crane arrived at F&ES in 2009, Greeley was in serious neglect. Taschner and Susan Wells, F&ES director of Finance and Administration, took photographs of the existing building and compared them to historical images to show Crane what Greeley had originally looked like — and what it had become.

“There was no adequate break space [or] community space left and what was left was so unusable it was impractical,” Taschner says. “The Dean was fabulous about all of this and made things happen. And once we got this into the architect’s hands, he used the photographs to restore the original intentions of Rudolph’s design.”

Renovating [Greeley] not only saved the building for the university, but has set a standard for the preservation of mid-century modern buildings all over the world

For many, including Taschner, Williams’ innovative reimaging of the main lobby — adhering to Rudolph’s principles while modernizing the building for the 21st century — has fundamentally changed the Greeley community.

“You go up there and people are eating lunch, they’re sitting in the lobby on their computers. They hang out; they interact; they have small meetings. It’s really a community now,” Taschner says. “I think that a lot of the science that comes out of there is fostered by that collaborative environment.”

The renovation restores Rudolph’s vision for an open plan and communal meeting spaces.

The renovation restores Rudolph’s vision for an open plan and communal meeting spaces.

Rennovated meeting room.

Rennovated meeting room.

Current office space detail.

Current office space detail.

Current lab space detail.

Current lab space detail.

The Center for Green Chemistry and Green Enginnering's new lab space.

The Center for Green Chemistry and Green Enginnering's new lab space.

Newly rennovated shared lab space on the north side of Greeley Lab.

Newly rennovated shared lab space on the north side of Greeley Lab.

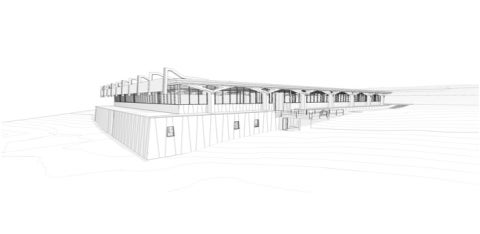

Architectual rendering of Greeley Laboratory.

Architectual rendering of Greeley Laboratory.