Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

Tom Siccama, 78, a revered professor of forest ecology at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies whose field lessons in the forests and landscapes of New England were a defining part of life for generations of F&ES and Yale College students — and, for many, life-changing events — died on Oct. 3 after a long illness.

Beloved for his quirky sense of humor and plainspoken manner, he was also considered one of the preeminent experts on the forest ecosystems of the northeastern U.S., publishing more than 120 research papers and developing an encyclopedic knowledge of the region’s soils and plants, geography and surface geology.

For Siccama, who joined the F&ES faculty in 1967 and continued to teach as Professor Emeritus after his retirement in 2006, the natural world was always the best classroom because it allowed students to understand the complexities of ecology through first-hand observation and by getting their hands dirty.

Whether it was during an afternoon hike in the woods of Connecticut or during annual trips to the forests of Puerto Rico, Siccama shined in the field, inspiring students with passionate lessons on how those natural spaces “work,” recalls Andrew Richardson ’98 M.F. ’03 Ph.D., who now teaches organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard.

“All of [these lessons], he taught, could be figured out through careful observation, knowledge of natural history and an understanding of some basic ecology, and by digging a hole in the ground or coring some trees,” Richardson said. “I think that this was a revelation for many of us.”

Born in Rahway, N.J., Siccama spent much of his childhood at his grandparents’ farm in southern New Jersey, an experience that nurtured his love of nature and the outdoors. During those years, he was also exposed to the region’s Pine Barren forests. In later years, he called a relic stand of pitch pines in Wallingford, Conn. his favorite trees because they reminded him of those forests of his youth.

In 1966, after earning a Ph.D. from the University of Vermont, Siccama accepted a postdoctoral position at the Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study, a pioneering research project based at a 3,160-hectare reserve in New Hampshire’s White Mountain National Forest. He would remain a part of that research project for the rest of his life.

At Hubbard Brook he also formed an important relationship with Herbert Bormann, who had joined the Yale faculty in 1966 and would also become an iconic figure at F&ES.

“Herb and I hit it off because we both like plants and the woods, critters and trees,” Siccama told an interviewer in 2009. “I got interested in collecting data about trees on… IBM punch cards. They made a special position for me at Yale, because I like computers and nobody else could program those old machines. I was useful in the woods, too.”

Siccama’s research focused on the study of soils, particularly the chemistry of the forest floor and long-term patterns in forest systems. For one of his studies, he determined that rain was dropping lead in the forest soils at Hubbard Brook. After collecting lead measurements across the region, Siccama and other researchers found that the highest concentrations were located along the Interstate-95 corridor — a discovery that would contribute to the federal government’s decision to remove lead from gasoline.

His research on the nutrient dynamics of the vegetation and soils conducted over nearly five decades helped to establish Hubbard Brook as the world’s leading study on forested ecosystems. The results from his scholarship informed public policy debates regarding acid rain, sustainable forestry, and climate change.

His collection and conservation of long-term data at Hubbard Brook not only established an invaluable baseline by which to measure the impact of environmental stressors on these forests but also inspired former students to carry on his work.

Beloved for his quirky sense of humor and plainspoken manner, he was also considered one of the preeminent experts on the forest ecosystems of the northeastern U.S., publishing more than 120 research papers and developing an encyclopedic knowledge of the region’s soils and plants, geography and surface geology.

For Siccama, who joined the F&ES faculty in 1967 and continued to teach as Professor Emeritus after his retirement in 2006, the natural world was always the best classroom because it allowed students to understand the complexities of ecology through first-hand observation and by getting their hands dirty.

Whether it was during an afternoon hike in the woods of Connecticut or during annual trips to the forests of Puerto Rico, Siccama shined in the field, inspiring students with passionate lessons on how those natural spaces “work,” recalls Andrew Richardson ’98 M.F. ’03 Ph.D., who now teaches organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard.

“All of [these lessons], he taught, could be figured out through careful observation, knowledge of natural history and an understanding of some basic ecology, and by digging a hole in the ground or coring some trees,” Richardson said. “I think that this was a revelation for many of us.”

Born in Rahway, N.J., Siccama spent much of his childhood at his grandparents’ farm in southern New Jersey, an experience that nurtured his love of nature and the outdoors. During those years, he was also exposed to the region’s Pine Barren forests. In later years, he called a relic stand of pitch pines in Wallingford, Conn. his favorite trees because they reminded him of those forests of his youth.

In 1966, after earning a Ph.D. from the University of Vermont, Siccama accepted a postdoctoral position at the Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study, a pioneering research project based at a 3,160-hectare reserve in New Hampshire’s White Mountain National Forest. He would remain a part of that research project for the rest of his life.

At Hubbard Brook he also formed an important relationship with Herbert Bormann, who had joined the Yale faculty in 1966 and would also become an iconic figure at F&ES.

“Herb and I hit it off because we both like plants and the woods, critters and trees,” Siccama told an interviewer in 2009. “I got interested in collecting data about trees on… IBM punch cards. They made a special position for me at Yale, because I like computers and nobody else could program those old machines. I was useful in the woods, too.”

Siccama’s research focused on the study of soils, particularly the chemistry of the forest floor and long-term patterns in forest systems. For one of his studies, he determined that rain was dropping lead in the forest soils at Hubbard Brook. After collecting lead measurements across the region, Siccama and other researchers found that the highest concentrations were located along the Interstate-95 corridor — a discovery that would contribute to the federal government’s decision to remove lead from gasoline.

His research on the nutrient dynamics of the vegetation and soils conducted over nearly five decades helped to establish Hubbard Brook as the world’s leading study on forested ecosystems. The results from his scholarship informed public policy debates regarding acid rain, sustainable forestry, and climate change.

His collection and conservation of long-term data at Hubbard Brook not only established an invaluable baseline by which to measure the impact of environmental stressors on these forests but also inspired former students to carry on his work.

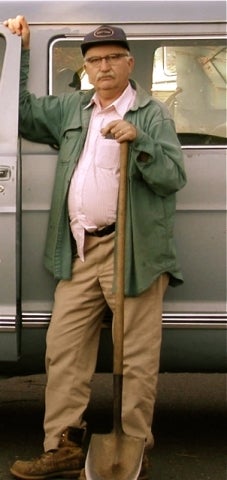

In 1992, Tom Siccama (with shovel) and several students celebrate the 25th anniversary of his “Terrestrial Ecosystems” course.

In 1992, Tom Siccama (with shovel) and several students celebrate the 25th anniversary of his “Terrestrial Ecosystems” course.

At F&ES, he introduced students to local plants and soils. His crash course in plant identification would become a defining piece of “MODS,” the School’s three-week summer orientation course. Four times he received the School’s top teaching and advising award.

Former students still recall trailing Siccama as he hiked briskly over wooded landscapes and, at break-neck speed, described the surrounding flora, explained how all the natural systems were connected, and shared his wisdom on how to read nature.

Sometimes those lessons didn’t end when the hike was over, recalled Jane Sokolow ’80 M.F.S. “We’d be in a bus, or on a truck with a couple of students, and we’d be rolling along I-91 or 95, driving at 65 miles per hour, and Tom would be identifying plants as we drove by!” she said. “They were gone before we even got a look at them! But everything was a teaching moment for him. Which is what makes a great teacher.”

On one occasion, after another faculty member challenged Siccama’s conviction that soil is “like a sponge,” Siccama, along with Richardson, set up an experiment in the hallway of Greeley Memorial Lab to test the theory. In a metal trough, they placed organic soils of different densities and sponges, poured water over them, and then used a hydrometer to measure the rate of water flow through the different mediums. They found that soils indeed act like sponges, attenuating the hydrological input and reducing peak flow. (The findings were eventually published in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association.)

This sort of “hallway science” typified Siccama’s ability to turn any situation into an opportunity to collect meaningful data and learn something new, said David Skelly, a professor of ecology at F&ES who for many years worked alongside Siccama.

“This sort of learning through action has become much more in vogue in recent years, but Tom never saw another way to do it,” Skelly said. “For him, that was the only way to do it.

“Tom changed the lives of so many of our students just by his example. Just by getting them into the field and showing them what was possible. He had a real gift for picking out the elements in the environment around you that could change how you see the world.”

Tom Siccama spent the last 50 days of his life in hospice care, said Ellen Denny ’97 M.F.S., who managed Siccama’s lab for several years and remained close with Tom and his family. During those final weeks, she said, he received more than 150 letters from colleagues and former students offering their love, respect, and gratitude.

“Tom lives on in so many people,” said Denny, a monitoring design and data coordinator for USA National Phenology Network. “He influenced so many lives and so many people loved him. What better tribute to a life well-lived?”

He is survived by his wife of 52 years, Judith Siccama of Shelburne, Vermont; his daughter, Carolyn Siccama, and her husband, Chris Trapeni; his granddaughter, Carly Trapeni; a sister-in-law, Sharon Roa, and her husband Glen Roa; a brother-in-law, George Pillsbury, and his wife, Celine Pillsbury; and his cat, Willow.

A private ceremony will be held to celebrate his life. In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to The Shore Line Trolley Museum, 17 River Street, East Haven, CT 06512.

Former students still recall trailing Siccama as he hiked briskly over wooded landscapes and, at break-neck speed, described the surrounding flora, explained how all the natural systems were connected, and shared his wisdom on how to read nature.

Sometimes those lessons didn’t end when the hike was over, recalled Jane Sokolow ’80 M.F.S. “We’d be in a bus, or on a truck with a couple of students, and we’d be rolling along I-91 or 95, driving at 65 miles per hour, and Tom would be identifying plants as we drove by!” she said. “They were gone before we even got a look at them! But everything was a teaching moment for him. Which is what makes a great teacher.”

On one occasion, after another faculty member challenged Siccama’s conviction that soil is “like a sponge,” Siccama, along with Richardson, set up an experiment in the hallway of Greeley Memorial Lab to test the theory. In a metal trough, they placed organic soils of different densities and sponges, poured water over them, and then used a hydrometer to measure the rate of water flow through the different mediums. They found that soils indeed act like sponges, attenuating the hydrological input and reducing peak flow. (The findings were eventually published in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association.)

This sort of “hallway science” typified Siccama’s ability to turn any situation into an opportunity to collect meaningful data and learn something new, said David Skelly, a professor of ecology at F&ES who for many years worked alongside Siccama.

“This sort of learning through action has become much more in vogue in recent years, but Tom never saw another way to do it,” Skelly said. “For him, that was the only way to do it.

“Tom changed the lives of so many of our students just by his example. Just by getting them into the field and showing them what was possible. He had a real gift for picking out the elements in the environment around you that could change how you see the world.”

Tom Siccama spent the last 50 days of his life in hospice care, said Ellen Denny ’97 M.F.S., who managed Siccama’s lab for several years and remained close with Tom and his family. During those final weeks, she said, he received more than 150 letters from colleagues and former students offering their love, respect, and gratitude.

“Tom lives on in so many people,” said Denny, a monitoring design and data coordinator for USA National Phenology Network. “He influenced so many lives and so many people loved him. What better tribute to a life well-lived?”

He is survived by his wife of 52 years, Judith Siccama of Shelburne, Vermont; his daughter, Carolyn Siccama, and her husband, Chris Trapeni; his granddaughter, Carly Trapeni; a sister-in-law, Sharon Roa, and her husband Glen Roa; a brother-in-law, George Pillsbury, and his wife, Celine Pillsbury; and his cat, Willow.

A private ceremony will be held to celebrate his life. In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to The Shore Line Trolley Museum, 17 River Street, East Haven, CT 06512.

– Kevin Dennehy kevin.dennehy@yale.edu 203 436-4842

Published

October 7, 2014