Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

The two professors walked to the front of the room on the first day of class and made an odd request: arm wrestle the person next to you.

“The people who get the opponent’s hand to touch the table the most times in 30 seconds win — go!”

The class of 120 students, many newly acquainted, obediently engaged in a test of strength until they were informed to stop. The two professors, Julie Zimmerman and Paul Anastas, then positioned themselves, locked hands, and began to arm wrestle — a bit differently. They took turns easily pinning each other’s hand to the table for 30 seconds before turning to the class and declaring, “We win!”

This was illustrative of how this course works — how students will think differently. After all, the professors never told the students this was a test of strength; it was a preconception that the students brought to the situation. It was their own intellectual baggage that they brought to problem-solving, restricting their ability to think differently.

This is “Perspectives,” not only a course but a shared experience. It’s a requirement for all first-year students in the Master of Environmental Management (M.E.M.) program and was developed last year as part of the curriculum that builds common foundational skills. Students are exposed to a wide range of ideas about the challenges and opportunities presented within environmental management through open discussion, fostering a shared understanding of the critical nature of interdisciplinary approaches.

At the center of the course is the concept of systems thinking, a way of understanding the inter-connections that exist in most of our greatest challenges — the climate, biodiversity, water and beyond. Common teaching methods don’t rely on systems thinking, but rather the traditional scientific method of reductionism — holding everything constant and changing one variable.

Sometimes, to truly understand a challenge or opportunity, you must look at its entirety, as a system. Then, by understanding all of the parts and how they interact, one can determine the best place to intervene.

“If you neglect to consider connections in the system, you often come up with a solution that causes unintended consequences — problems somewhere else that you didn’t account for,” says Zimmerman, professor of green engineering and senior associate dean of academic affairs at the Yale School of the Environment.

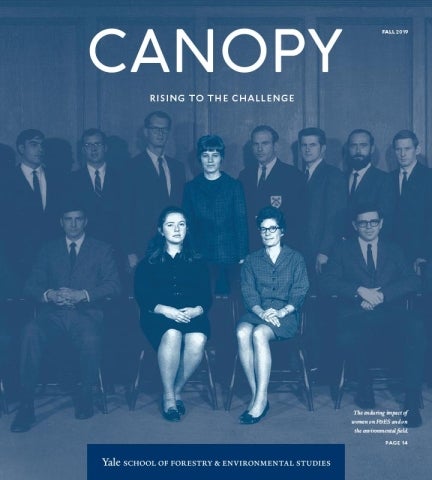

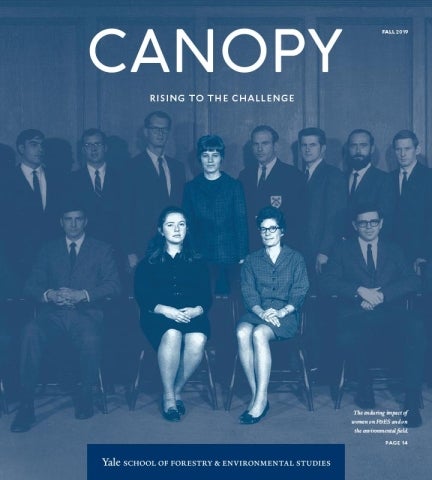

This article was originally published in the fall 2019 edition of Canopy magazine

This article was originally published in the fall 2019 edition of Canopy magazine

“This is a framework for how you approach complex problems — what we call ‘wicked problems,’” added Anastas, the Teresa and H. John Heinz III Professor in the Practice of Chemistry for the Environment. “They’re complex, they’re interconnected, they don’t lend themselves to simple solutions. For hundreds of years, we’ve looked at one aspect of a problem and tried to study it. This is taking a step back and understanding the interrelationships at play here.”

Quandaries regarding arm wrestling aren’t the “wicked problems” these students will face, of course. What they face are thorny environmental issues that cut across social, political, and economic boundaries, require multiple public and private agencies, and continually evolve with varying levels of conflict.

To that end, “Perspectives” is taught through the lens of a single case study — this year, the proposed Bristol Bay Pebble Mine in Alaska, crowdsourced from the incoming M.E.M. class themselves. For more than a decade, a complex fight has played out over a proposed open-pit copper and gold mine in southwest Alaska. Predictably, proponents of the plan have touted the potential economic benefits of the mine and decreased reliance on foreign natural resources, while those against the proposal fear the environmental and social consequences. The land being tabbed for the proposed mine covers thousands of acres of wetlands, including waters that are home to the world’s largest salmon run — critical for local jobs, culture, and tourism.

Efforts to begin building the mine have been stymied, primarily due to a 2014 ruling by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that blocked the proposal over environmental concerns. After several years of litigation, however, the EPA withdrew the initial ruling this past summer and has begun the process of reviewing the permit again.

In each class, students hear from a new voice. Guest speakers include Verner Wilson III ’15 M.E.M., senior oceans campaigner for Friends of the Earth's Oceans & Vessels program and a Bristol Bay native; Dennis McLarren, the former EPA Region 10 Administrator when the permit was denied in 2014; Mike Heatwole, the vice president for public affairs of the Pebble Partnership, the mining company pursuing the permit; and four local women fishermen in Bristol Bay. The class also hosted a screening of a documentary about the conflict, “The Wild,” at Criterion Cinemas in New Haven, where the flimmaker, Mark Titus, was on hand to field questions from students and the public.

Each week after listening to the guest speaker, students break into discussion groups to recalibrate their understanding of the case based on what they’ve heard, relating to their classmates how their views may have changed after hearing a new perspective. In particular, they are asked to use systems-thinking tools to describe and understand the complexity of the system, which evolves each week with every new perspective brought by the guest speakers. Second-year M.E.M. students are assigned to work with each group and then meet collectively with Zimmerman and Anastas to begin shaping the discussion for the following week.

Though the Pebble Mine case may not hit on a particular area of interest for each student, the professors believe processing new perspectives will be relevant for any “wicked problem” students will face in their careers.

“We want them to think about this important case,” Zimmerman said, “but what we really want is for them to think about how they are thinking about the case.”

“Whether you become a scientist, an activist, an economist — whatever it may be — you need to be able to understand and process other perspectives,” added Anastas.

Elizabeth Himschoot ’21 M.E.M. had a unique perspective on the Pebble Mine case already. She not only took the course, but is also a native of Dillingham, Alaska — located in the heart of the Bristol Bay region. She’s studying land conservation and management with a focus on the rights of indigenous peoples and hopes to return to the Arctic to help protect the ecosystems for the people and wildlife.

Himschoot’s perspective may be rooted in personal experience, but she acknowledges the value of taking a step back to understand differing viewpoints.

“My classmates include people who have lobbied against extractive industries and protected wildlife, and there are people who have worked for extractive industries and the energy industry,” said Himschoot. “Some of my classmates are from different countries and cultures, which affects their personal perspectives.”

“Listening to my classmates and guest speakers provides me with a new understanding of these various perspectives and the ability to accept those views, even if I don’t agree with them,” she continued.

Perspectives are being shared outside the classroom, as well. Himschoot and Anelise Zimmer ’21 M.E.M., who is also from Alaska, hosted a discussion group with their classmates to explain the geography, culture, lifestyle, and industry of Bristol Bay. Himschoot said a number of her classmates participated, with many reaching out after the discussion for additional information.

“It’s a way to help our classmates understand Bristol Bay isn’t just a name on a page, but that it’s a place where humans and nature must coexist,” said Himschoot.

It’s a system where, unlike arm wrestling, there isn’t one goal.

The parts must work together to form a genuine win-win solution.

This article was originally published in the fall 2019 edition of Canopy magazine

This article was originally published in the fall 2019 edition of Canopy magazine