Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

In June of 1990, with the Soviet Union a year from collapse but already crumbling, U.S. President George H. W. Bush and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev made a remarkable announcement.

The rival nations had agreed to create the Beringia Heritage International Park, a vast trans-boundary park spanning Soviet and Alaskan lands on both sides of the Bering Strait. Although the park was never formalized, the very concept was both a conservation milestone and a testament to the thawing of the Cold War.

The rival nations had agreed to create the Beringia Heritage International Park, a vast trans-boundary park spanning Soviet and Alaskan lands on both sides of the Bering Strait. Although the park was never formalized, the very concept was both a conservation milestone and a testament to the thawing of the Cold War.

Five thousand miles to the east, Beringia was also launching a career. Margaret Williams M.E.Sc '93 was a senior at Smith College, studying Russian language and environmental studies, when she first learned of the proposed park. She was captivated. “I thought it was the most incredible moment,” she says now, “to see two enemy countries creating peace through the conservation of nature.” Somehow, Williams vowed, she would visit Beringia.

Williams got her chance in 1992. While a Masters student at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, she received funding to spend the summer teaching English and managing a remote field camp in a zapovednik, one of Russia’s famed protected areas.

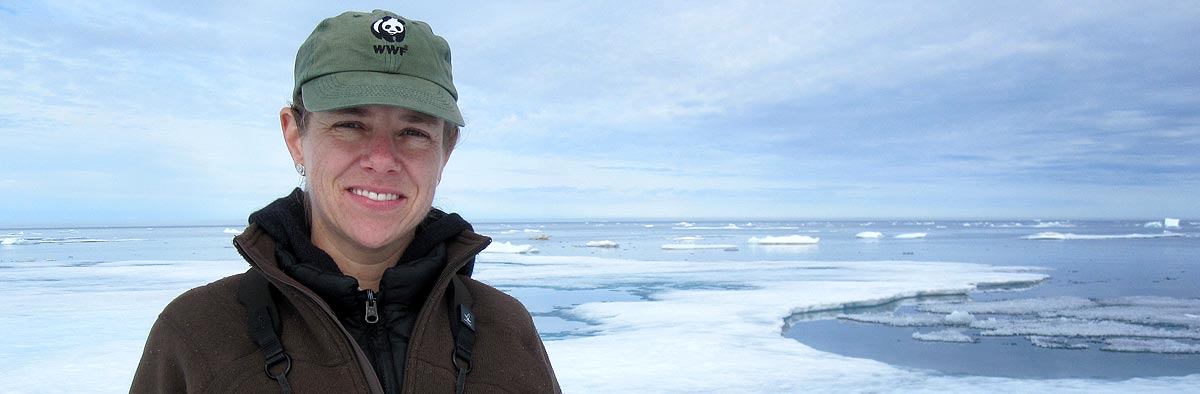

“What I saw there blew my mind,” recalls Williams, who is now managing director of the World Wildlife Fund’s Arctic Program. “The nature reserve was enormous — there were brown bears, Steller’s sea eagles, huge salmon runs — and yet the physical infrastructure was so poor. The lights barely operated, nobody had computers, and it was all very dilapidated.” The Soviet Union had by then disintegrated once and for all, and with it went most of Russia’s conservation funding.

Through a fellowship from the Echoing Green Foundation, Williams spent three summers in Magadansky Zapovednik in the Russian Far East, and another in Kostomukshsky Zapovednik in the northwestern part of the country. Watching scientists and managers scramble to hold their protected areas together on limited funding, she felt inspired to help remedy the penurious state of Russian conservation.

Williams got her chance in 1992. While a Masters student at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, she received funding to spend the summer teaching English and managing a remote field camp in a zapovednik, one of Russia’s famed protected areas.

“What I saw there blew my mind,” recalls Williams, who is now managing director of the World Wildlife Fund’s Arctic Program. “The nature reserve was enormous — there were brown bears, Steller’s sea eagles, huge salmon runs — and yet the physical infrastructure was so poor. The lights barely operated, nobody had computers, and it was all very dilapidated.” The Soviet Union had by then disintegrated once and for all, and with it went most of Russia’s conservation funding.

Through a fellowship from the Echoing Green Foundation, Williams spent three summers in Magadansky Zapovednik in the Russian Far East, and another in Kostomukshsky Zapovednik in the northwestern part of the country. Watching scientists and managers scramble to hold their protected areas together on limited funding, she felt inspired to help remedy the penurious state of Russian conservation.

Russian Conservation News is the strongest indicator of Margaret's remarkable ability to create something out of nothing with the force of her intellect and energy.

Williams moved to Moscow, where a charismatic friend from Yale, Eugene Simonov M.E.Sc '93 , had co-founded an NGO called the Biodiversity Conservation Center. The BCC lacked offices — Williams remembers “a tiny rented apartment, people coming and going and cooking meals at odd times of the day, laundry hung up in hallways and bathrooms, everyone talking and smoking wildly” — but not ambition. Soon after her arrival in Moscow, Williams began editing and publishing Russian Conservation News, a quarterly newsletter that contained reports from scientists and conservationists, which eventually attracted more than 1,000 subscribers. Sometimes, Williams recalls, she would receive articles written in baroque cursive pencil, with a grainy black-and-white photo thrown in for good measure.

"To me, Russian Conservation News is the strongest indicator of Margaret's remarkable ability to create something out of nothing with the force of her intellect and energy,” says Fred Strebeigh, who wrote aboutWilliams’ and Simonov’s efforts in 2010 for Environment Yale. “Taken as a whole, it is effectively the great book in English on Russian nature conservation since the fall of the Soviet Union.”

In 1996, Williams took Russian Conservation News across the world to Washington, D.C., where she founded the BCC’s western sister office. Her work in D.C. soon brought her into contact with the nearby World Wildlife Fund, which had developed an interest in Williams’ longtime fixation, the Bering Sea. The Bering, and the adjacent Chukchi Sea, seemed a natural fit for the WWF — their rich Arctic waters are home to a menagerie that includes gray whales, polar bears, and enormous pollock fisheries — and the group hired Williams to assess the possibility of establishing a Bering Sea office.

As it turned out, she was creating her own job. A decade and a half later, Williams remains the Anchorage-based director of WWF’s Arctic program, where she works tirelessly to defend the Bering, Beaufort and Chukchi seas and the humans who depend on them.

That’s fortunate, because America’s Arctic waters need all the help they can get: between fishing trawlers dragging their nets across vulnerable deep-sea habitat, the persistent threat of offshore oil and gas drilling, and the climate change that is simultaneously destabilizing icy ecosystems and exposing the Arctic to industrial activity, it would be difficult to find a more precarious eco-region on the planet.

"To me, Russian Conservation News is the strongest indicator of Margaret's remarkable ability to create something out of nothing with the force of her intellect and energy,” says Fred Strebeigh, who wrote aboutWilliams’ and Simonov’s efforts in 2010 for Environment Yale. “Taken as a whole, it is effectively the great book in English on Russian nature conservation since the fall of the Soviet Union.”

In 1996, Williams took Russian Conservation News across the world to Washington, D.C., where she founded the BCC’s western sister office. Her work in D.C. soon brought her into contact with the nearby World Wildlife Fund, which had developed an interest in Williams’ longtime fixation, the Bering Sea. The Bering, and the adjacent Chukchi Sea, seemed a natural fit for the WWF — their rich Arctic waters are home to a menagerie that includes gray whales, polar bears, and enormous pollock fisheries — and the group hired Williams to assess the possibility of establishing a Bering Sea office.

As it turned out, she was creating her own job. A decade and a half later, Williams remains the Anchorage-based director of WWF’s Arctic program, where she works tirelessly to defend the Bering, Beaufort and Chukchi seas and the humans who depend on them.

That’s fortunate, because America’s Arctic waters need all the help they can get: between fishing trawlers dragging their nets across vulnerable deep-sea habitat, the persistent threat of offshore oil and gas drilling, and the climate change that is simultaneously destabilizing icy ecosystems and exposing the Arctic to industrial activity, it would be difficult to find a more precarious eco-region on the planet.

We have a huge opportunity to use the best science, traditional knowledge, and smart policies, to get Arctic management right.

Williams’ eclectic work at the World Wildlife Fund reflects the diversity of those challenges. She has held collaborative workshops on fur seal conservation in the Pribilof Islands, helped hammer out international treaties for the management of polar bears, and convinced Russian fishermen to reduce the bycatch of short-tailed albatrosses.

“We showed them that you could calculate the economic costs of lost bait, as well as the opportunity lost when your hook comes up with a bird instead of a fish,” Williams says of the latter project. “Eventually, the largest long-line fishing company in Kamchatka was making the case for conservation.”

That conservation model — helping individuals and businesses understand the financial logic underpinning sustainable practices — now drives Williams’ work on a challenge far more daunting than bycatch: climate change. Where once WWF Arctic sought to mobilize public passion with stories of drowning polar bears and inundated coastal communities, now it’s just as likely to stress the economic and security aspects of climate change.

And, like so many other conservationists, Williams has changed her focus from preventing climate change outright to softening its blows.

“While we still desperately need to reduce CO2 emissions, we also have to think about how to help beleaguered Arctic ecosystems weather the climate storm,” Williams says. “Given the dramatic climate change impacts that are already occurring, we have to work even harder to eliminate other stresses to nature, such as oil spills, overfishing, and habitat fragmentation.”

Fortunately, Williams says, the Arctic still contains vast areas of intact habitat. “We’re at a crossroads for development,” she says. “We have a huge opportunity to use the best science, traditional knowledge, and smart policies, to get Arctic management right.” Whether decision-makers embrace that opportunity will help determine the fate of Arctic wildlife and communities.

“We showed them that you could calculate the economic costs of lost bait, as well as the opportunity lost when your hook comes up with a bird instead of a fish,” Williams says of the latter project. “Eventually, the largest long-line fishing company in Kamchatka was making the case for conservation.”

That conservation model — helping individuals and businesses understand the financial logic underpinning sustainable practices — now drives Williams’ work on a challenge far more daunting than bycatch: climate change. Where once WWF Arctic sought to mobilize public passion with stories of drowning polar bears and inundated coastal communities, now it’s just as likely to stress the economic and security aspects of climate change.

And, like so many other conservationists, Williams has changed her focus from preventing climate change outright to softening its blows.

“While we still desperately need to reduce CO2 emissions, we also have to think about how to help beleaguered Arctic ecosystems weather the climate storm,” Williams says. “Given the dramatic climate change impacts that are already occurring, we have to work even harder to eliminate other stresses to nature, such as oil spills, overfishing, and habitat fragmentation.”

Fortunately, Williams says, the Arctic still contains vast areas of intact habitat. “We’re at a crossroads for development,” she says. “We have a huge opportunity to use the best science, traditional knowledge, and smart policies, to get Arctic management right.” Whether decision-makers embrace that opportunity will help determine the fate of Arctic wildlife and communities.

Ben Goldfarb is a 2013 graduate of the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, where he served as editor of Sage Magazine. His writing has appeared in The Guardian, High Country News, OnEarth Magazine, Yale Environment 360, and elsewhere.

Published

October 1, 2013