Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

Gao Yufang

Gao Yufang

Global efforts to protect elephant populations today are hampered by contentious disagreement over the best conservation policy, write a team of leading researchers from 14 institutions, including Yale. On the one side are those calling for an international ban on the ivory trade. On the other are those who believe that a closely regulated trade is the only way to save elephants.

One of the authors is Gao Yufang, a doctoral student in the combined degree program between the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies and Yale’s Department of Anthropology, who has studied how human values affect decisions by stakeholders at every step of the ivory trade, from the local communities where elephants are killed to the Chinese communities where the ivory products are purchased.

In an interview Gao, who is from China, talks about how different perspectives and values are shaping the very definition of the problem, and how humankind might be able to slow an epidemic of poaching that, according to some scientists, is claiming as many as 20,000 elephants every year. If conservation leaders don’t take the time to understand and reconcile these different perspectives and values, he said, it will be impossible to craft meaningful long-term solutions.

Indeed, he said, it will be elephants that suffer the most.

In the new article, you argue that the debate over whether to ban the ivory trade is hampering the greater goal of protecting elephants. How so?

Yufang Gao: Wildlife conservation is fundamentally about people making decisions, and in most situations, decisions are matters of political struggle over different values. I started researching the ivory trade in 2012 because at that time I was shocked to see that on the one hand African elephants were threatened by poaching and illegal ivory trade, on the other hand, people were in disagreement and unable to organize collective and effective conservation efforts. The situation has improved in many ways, but the deadlock over ivory policies continues.

To have a problem, one must first have a goal, which is their guided values, whether they are aware or not. A problem exists when there is a discrepancy between the perceived reality and the valued goal. There are many participants involved in the issue of international ivory trade. People’s different perspectives and values influence how they understand the problem and think about possible solutions. The deadlock confronting us reflects that our current decision-making process is not able to reconcile the different perspectives and values. Our article offers an approach to deal with the obstacle, and personally I see it as an invitation to conservation scientists to consider alternative governance structures and processes that can integrate science, policy, and decision-making in a better way to secure our common interest.

For many international organizations this call for banning the ivory trade has become the predominant strategy…

Gao: Yes, that’s the dominant perspective now, and it has gained a lot of momentum. Conservation organizations and animal welfare groups want to ban all forms of trade in ivory. They argue that if there is a legal trade, there will be no way to distinguish illegal ivory that enters the trade, and that it would increase the difficulty in implementing laws and regulations. Also, they believe that if we declare all ivory trade illegal it will help people understand that buying ivory is not socially acceptable, which will make it easier to reduce the demand and shut down the market.

What about the other side of the debate?

Gao: Well, those who are in favor of having a regulated trade say, ‘What about local communities who bear the cost of living with elephants?’ They argue that the ivory trade can be an important source of income to support local communities and conservation initiatives. There are also concerns that forbidding the ivory trade won’t be useful because the entire market will be done illegally and also because law enforcement in many countries tends to be ineffective. If you ban the trade, it goes to the black market and it may push the ivory price to higher levels.

Now, I don’t intend to represent either viewpoint, but I can see how both arguments make sense in some ways. As we write in the paper, it’s important to recognize and understand people's different perspectives and their underlying values because they determine alternate definitions of the problem and possible solutions.

You’ve done extensive research on how human values and perspectives affect their behavior — including among different groups involved at different steps of the international ivory trade. What have you learned about how values and perspectives affect conservation?

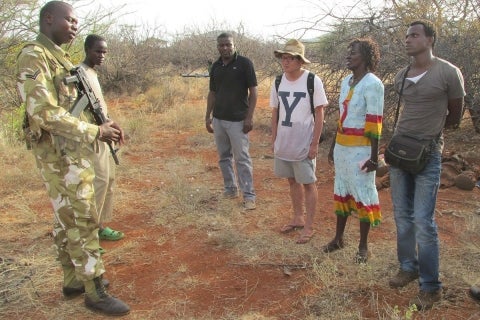

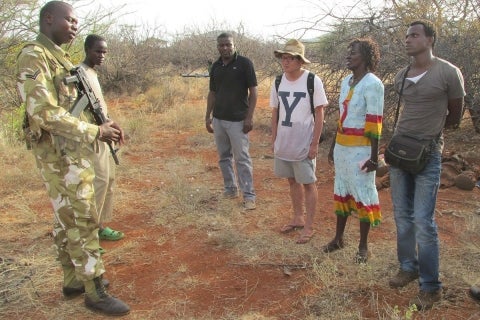

Gao Yufang in Kenya, where he researched cultural viewpoints on the ongoing slaughter of African elephants.

Gao Yufang in Kenya, where he researched cultural viewpoints on the ongoing slaughter of African elephants.

Gao: Conservation problems do not exist in a vacuum. They happen in intricate, evolving social contexts. Different individuals and groups with their subjective perspectives interact in various situations. They use the resources they have through various strategies to achieve the outcomes they value. And, their interactions have effects in the broader social and decision-making processes, which, in turn, also structure their interactions. People tend to interact with each other in a way that they presume would maximize their perceived interests. Analyzing people’s perspectives, including their identities, value demands, and expectations, is key to understanding the social context of a conservation problem. For me, this requires understanding the things that people go after in their lives, whether it’s power or wealth, wellbeing or affection, knowledge or skill, rectitude or respect.

Empirical science is useful and necessary to problem-solving, but science alone is not going to help us solve a complex problem like the ivory trade. Our knowledge of the problem we are dealing with is always incomplete and full of uncertainties. I also don't think we can separate knowledge making from value judgment. We scientists are also humans and we are also part of the social interaction processes. We must be more reflective of our perspectives and values.

How might an alternative process work?

Gao: Well, it's too complex to explain in a few sentences. Experts in other areas have harvested a lot of useful experience on how to overcome the gridlock in natural resource policymaking through upgrading the social and decision-making processes. Here I would like to emphasize that the very first step is to recognize the different perspectives and related value outlooks. Differences are not a danger to collective efforts; the real danger is the unawareness of differences and the unwillingness to recognize differences. Our article offers a possible way to help people understand their differences. Based on a genuine recognition of different perspectives, values, and related modes of cognitive and practical problem-solving, we can then integrate scientific and other types of knowledge into policies and make better decisions. Rather than relying on a single, centralized authority, I believe we must create new arenas to facilitate the intercultural communication processes on various levels of our society.

The paper cites examples in which trust building approaches helped people with different viewpoints reach compromise — such as the Paris climate accord. How can those lessons be applied in this case?

Gao: I think what the examples teach us is the importance of interpersonal communication in building trust and mutual respect. Even though we may have different perspectives and values, fundamentally we are all humans. We also share a lot of similarities. We should treat people as real persons rather than labels.

How can any process, no matter how inclusive, overcome the fact that so much can be gained by killing these animals?

Gao: Well, the relationships between local people and elephants are complex. In some areas, elephants can pose a great danger to local peoples. Some local people will also kill an elephant if outsiders offer them a lot of money. But, still, this is already a very simplified understanding of the local situation. It is important to respect the values of local people. We can’t decide between the wellbeing of local people and the wellbeing of elephants together — they’re equally important. For me, it comes back to some fundamental questions: How should people coexist with elephants? Who gets to decide? Who is going to pay the cost of this coexistence?

There are different perspectives and values, but are they all equally valid and appropriate? I don’t think so. It is important to distinguish the special interest and the common interest. Different people may have different criteria to make the judgments. From my perspective, living beings, whether humans or nonhumans, are all born equal, and an ideal society should recognize and safeguard the dignity of all living beings on Earth because we are all interdependent. This is my commitment. Local people’s demand for wellbeing and conservationists’ demand for saving elephants are both valid. But the demand for preserving ivory carving culture is inappropriate in this particular context because a culture that is based on the suffering of a living being is not a good culture. This is why I support the Chinese government to shut down its domestic ivory trade, which has for a long time been continued in the name of cultural heritage preservation... Rather than focusing on a single goal, our conservation policies and programs should accommodate multiple valid and appropriate objectives.

Later this month China will officially ban the trade of ivory in that country. How will that affect the situation?

Gao: China’s ivory ban in and of itself is not going to save the elephant. Early this year I have recommended that

ending the illegal ivory trade in China requires a holistic approach. The biggest obstacle that China is going to face is the implementation of the policy, and policy implementation in China is always hindered by many factors. Usually, it’s because the accountabilities and authorities are distributed across different bureaucratic agencies. Also, a lot of work needs to be done to ensure that the dictum from far-away Beijing is actually enforced locally, given that China is such a vast country... China alone cannot save the elephant. It’s a global issue, and countries in Africa, Asia, and the global community should collaborate to assure a sustainable future for the healthy coexistence between people and elephants. Let's build a broader coalition and work together.

Gao Yufang

Gao Yufang

Gao Yufang in Kenya, where he researched cultural viewpoints on the ongoing slaughter of African elephants.

Gao Yufang in Kenya, where he researched cultural viewpoints on the ongoing slaughter of African elephants.