Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

There is a reason that Silver Valley, Idaho, got its name. The steep cliffs that border the south fork of the Coeur d’Alene River, as it flows westward into the lowlands, were home to mining operations beginning in the 1880s. Silver came first, then lead and zinc. By the mid-1970s, the region contained the world’s four largest silver mines, which produced 47 percent of the silver in the United States, and 8 percent of its lead.

But there were consequences. The native coniferous forests were quickly cleared; the sulfur dioxide emissions from industry acidified the soil; tundra swans downstream were dying off. And then, in the 1970s, it was discovered that children in the region had remarkably high levels of lead in their blood. After one smelter’s pollution control mechanism caught fire, it was revealed that the 12,000 people, including thousands of children, faced persistent health problems.

“It was the worst lead poisoning epidemic associated with an industrial facility ever to occur in the U.S.,” recalls Ian von Lindern M.F.S. ’73, Ph.D. ’80, the co-founder and CEO of TerraGraphics Environmental Engineering, an Idaho-based firm that has worked on a range of environmental projects, from river restoration to water quality assessments, including the Silver Valley cleanup.

But there were consequences. The native coniferous forests were quickly cleared; the sulfur dioxide emissions from industry acidified the soil; tundra swans downstream were dying off. And then, in the 1970s, it was discovered that children in the region had remarkably high levels of lead in their blood. After one smelter’s pollution control mechanism caught fire, it was revealed that the 12,000 people, including thousands of children, faced persistent health problems.

“It was the worst lead poisoning epidemic associated with an industrial facility ever to occur in the U.S.,” recalls Ian von Lindern M.F.S. ’73, Ph.D. ’80, the co-founder and CEO of TerraGraphics Environmental Engineering, an Idaho-based firm that has worked on a range of environmental projects, from river restoration to water quality assessments, including the Silver Valley cleanup.

Almost all of the effective work that we end up doing is at the community level. You really have to work with the people.

For more than four decades, von Lindern has been involved with the cleanup of Silver Valley — including work that inspired his PhD thesis at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. And he has applied the lessons learned in Idaho to pollution sites across the world.

Von Lindern was a chemical engineer before he came to F&ES in 1971. At the time, the country was just starting to adopt stricter environmental regulations, including the National Environmental Policy Act in 1969. The Clean Air Act and National Ambient Air Quality standards would soon follow.

“I actually went to Yale with the idea of coming out of there and working for the EPA as a pollution control engineer,” he recalls. “I got in on the ground floor of the environmental regulatory system. There hadn't been many people in that field before.”

After earning his master’s degree, von Lindern became one of the first employees with the newly-created Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. And before long, something happened that would transform his career: Air pollution data from the Silver Valley smelters, now required by the Clean Air Act, started coming in. Those data sets would set the stage for von Lindern’s return to New Haven.

When he came back to F&ES for his Ph.D, his research focused on the design of better air pollution models in order to meet the new national lead standards. He used the Silver Valley case and its particulate matter emissions data as a case study. For the thesis, von Lindern consulted with his classmate Dana Tomlin M.Phil ’78, Ph.D. ’83, now professor of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) at F&ES, to develop sophisticated GIS analysis techniques that were quite new at the time. While von Lindern says those graphics “are really embarrassing today,” the research helped pioneer technology critical to much of today’s environmental research.

Von Lindern was a chemical engineer before he came to F&ES in 1971. At the time, the country was just starting to adopt stricter environmental regulations, including the National Environmental Policy Act in 1969. The Clean Air Act and National Ambient Air Quality standards would soon follow.

“I actually went to Yale with the idea of coming out of there and working for the EPA as a pollution control engineer,” he recalls. “I got in on the ground floor of the environmental regulatory system. There hadn't been many people in that field before.”

After earning his master’s degree, von Lindern became one of the first employees with the newly-created Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. And before long, something happened that would transform his career: Air pollution data from the Silver Valley smelters, now required by the Clean Air Act, started coming in. Those data sets would set the stage for von Lindern’s return to New Haven.

When he came back to F&ES for his Ph.D, his research focused on the design of better air pollution models in order to meet the new national lead standards. He used the Silver Valley case and its particulate matter emissions data as a case study. For the thesis, von Lindern consulted with his classmate Dana Tomlin M.Phil ’78, Ph.D. ’83, now professor of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) at F&ES, to develop sophisticated GIS analysis techniques that were quite new at the time. While von Lindern says those graphics “are really embarrassing today,” the research helped pioneer technology critical to much of today’s environmental research.

To implement some of the new technologies he had been working on, von Lindern co-founded TerraGraphics with his wife, Margrit von Braun, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Idaho, in 1984. One of their major projects was the ongoing cleanup at Silver Valley.

In addition to removing contaminated soil from every home in the community, the company monitored the blood levels of children in the region annually for three decades. While those tests stopped in 2002 — when lead levels were finally down to the national average — the company continues to monitor the project area, including regular medical checkups for community members. In fact, while the Silver Valley area remains a federal Superfund site, significant progress has been made so far — especially with respect to human health. “All of this is a model for how to respond to a community lead poisoning epidemic,” von Lindern says.

In the U.S., the threat of lead poisoning largely disappeared when the government decided to remove lead from gasoline, paint, and other consumer goods, von Lindern says. He calls it one of the nation’s “great public health stories.” But, he adds, “during those years the U.S. exported its entire lead industry overseas — much of it to developing countries. As a result, more kids are poisoned than ever before.”

So in recent years TerraGraphics has exported its cleanup strategies to lead-poisoning disaster sites around the world, including in Russia, the Dominican Republic, China, and Senegal.

In addition to removing contaminated soil from every home in the community, the company monitored the blood levels of children in the region annually for three decades. While those tests stopped in 2002 — when lead levels were finally down to the national average — the company continues to monitor the project area, including regular medical checkups for community members. In fact, while the Silver Valley area remains a federal Superfund site, significant progress has been made so far — especially with respect to human health. “All of this is a model for how to respond to a community lead poisoning epidemic,” von Lindern says.

In the U.S., the threat of lead poisoning largely disappeared when the government decided to remove lead from gasoline, paint, and other consumer goods, von Lindern says. He calls it one of the nation’s “great public health stories.” But, he adds, “during those years the U.S. exported its entire lead industry overseas — much of it to developing countries. As a result, more kids are poisoned than ever before.”

So in recent years TerraGraphics has exported its cleanup strategies to lead-poisoning disaster sites around the world, including in Russia, the Dominican Republic, China, and Senegal.

In 2010, when eight villages in Nigeria fell victim to a lead poisoning epidemic, von Lindern and his TerraGraphics team was called on to help with the response.

In 2010, when eight villages in Nigeria fell victim to a lead poisoning epidemic, von Lindern and his TerraGraphics team was called on to help with the response.

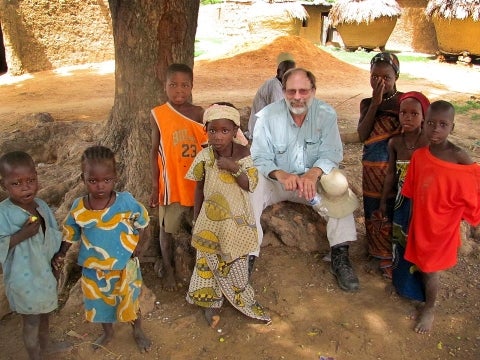

Four years ago, in Nigeria’s Zamfara province, eight villages fell victim to a lead poisoning epidemic. Initial reports indicated that 500 children died in a span of six months. In this case, the health threat was caused by gold, which contains about 10-percent lead and was being mined voraciously in the region as prices hit record highs.

After this epidemic was discovered, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control called on von Lindern’s TerraGraphics team to help. His team worked with Médecins Sans Frontières, an international medical and humanitarian aid organization, on medical services and the environmental response. Their cleanup plan involved an emergency phase, a remediation phase, and a biological monitoring phase, similar to the cleanup strategy used by von Lindern’s team in Idaho.

For his work in Nigeria, von Lindern and his company received the Green Star Award from the United Nations Environment Programme and the United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. It was the first private company to receive the honot, which is awarded biennially to organizations that are confronting environmental disasters.

“Our philosophy is probably a unique part of what we do,” von Lindern says. “Almost all of the effective work that we end up doing is at the community level. You really have to work with the people.

“It's important to do it that way because these cleanups have to endure.”

After this epidemic was discovered, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control called on von Lindern’s TerraGraphics team to help. His team worked with Médecins Sans Frontières, an international medical and humanitarian aid organization, on medical services and the environmental response. Their cleanup plan involved an emergency phase, a remediation phase, and a biological monitoring phase, similar to the cleanup strategy used by von Lindern’s team in Idaho.

For his work in Nigeria, von Lindern and his company received the Green Star Award from the United Nations Environment Programme and the United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. It was the first private company to receive the honot, which is awarded biennially to organizations that are confronting environmental disasters.

“Our philosophy is probably a unique part of what we do,” von Lindern says. “Almost all of the effective work that we end up doing is at the community level. You really have to work with the people.

“It's important to do it that way because these cleanups have to endure.”

Omar Malik is a 2013 graduate of the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, where he studied international environmental policy and climate change. He is an environmental performance analyst for the Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy and a freelance writer.

Published

October 4, 2013