Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

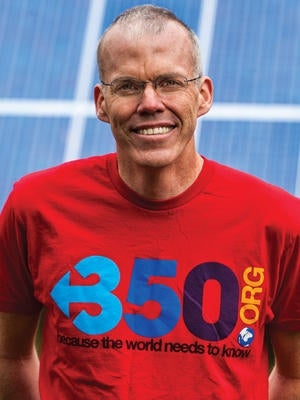

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben

This week, renowned author and environmentalist Bill McKibben delivered the Chubb Fellowship Lecture titled, “Simply Too Hot: The Desperate Science and Politics of Climate Change,” to a packed audience at Yale’s Woosley Hall.

McKibben is currently the Schumann Distinguished Scholar in Environmental Studies at Middlebury College and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His awards include the Right Livelihood Prize, the Ghandi Prize, the Thomas Merton Prize, the President’s Medal from the Geological Society of America, and the Lannan Prize for nonfiction writing. He has also received the prestigious Guggenheim and Lyndhurst Fellowships, and holds honorary degrees from 18 colleges and universities. The Boston Globe has called McKibben “America’s most important environmentalist.”

He began his career as a staff writer at The New Yorker. In 1989, at the age of 28, he published “The End of Nature,” widely considered the first book about global warming written for a broad audience. He has since published more than a dozen books, and continues to write for several publications, including the New York Review of Books, National Geographic, Rolling Stone, and Yale Environment 360. In 2008, he co-founded 350.org, the first planet-wide, grassroots climate change movement, which has organized some 20,000 marches and events worldwide. In 2014, biologists named a new species of woodland gnat, Megophthalmidia mckibbeni, in his honor.

The Chubb Fellowship, based at Timothy Dwight College, is designed to foster among the students at the college and across Yale University an interest in public affairs. In addition to the public lecture, Fellows meet with students and faculty during a meal, reception, or seminar.

We caught up with McKibben before his lecture to talk about the role of climate change activism during the Trump administration.

We’re here on an inauspicious day. This morning, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt announced a decision by the Trump administration to roll back the Clean Power Plan. How significant is today’s announcement?

Bill McKibben: Well, significant, but not unexpected. This has been the dream, not so much of Donald Trump, but of the Koch brothers and their ilk for a long time. Though Trump’s doing terrible things in other places, I think that the environmental damage would’ve been done no matter what Republican president was in charge of things. This is the long-time wish list of the fossil fuel industry, and one after another they’re rolling back the quite modest regulations that tried in any way to rein them in.

McKibben is currently the Schumann Distinguished Scholar in Environmental Studies at Middlebury College and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His awards include the Right Livelihood Prize, the Ghandi Prize, the Thomas Merton Prize, the President’s Medal from the Geological Society of America, and the Lannan Prize for nonfiction writing. He has also received the prestigious Guggenheim and Lyndhurst Fellowships, and holds honorary degrees from 18 colleges and universities. The Boston Globe has called McKibben “America’s most important environmentalist.”

He began his career as a staff writer at The New Yorker. In 1989, at the age of 28, he published “The End of Nature,” widely considered the first book about global warming written for a broad audience. He has since published more than a dozen books, and continues to write for several publications, including the New York Review of Books, National Geographic, Rolling Stone, and Yale Environment 360. In 2008, he co-founded 350.org, the first planet-wide, grassroots climate change movement, which has organized some 20,000 marches and events worldwide. In 2014, biologists named a new species of woodland gnat, Megophthalmidia mckibbeni, in his honor.

The Chubb Fellowship, based at Timothy Dwight College, is designed to foster among the students at the college and across Yale University an interest in public affairs. In addition to the public lecture, Fellows meet with students and faculty during a meal, reception, or seminar.

We caught up with McKibben before his lecture to talk about the role of climate change activism during the Trump administration.

We’re here on an inauspicious day. This morning, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt announced a decision by the Trump administration to roll back the Clean Power Plan. How significant is today’s announcement?

Bill McKibben: Well, significant, but not unexpected. This has been the dream, not so much of Donald Trump, but of the Koch brothers and their ilk for a long time. Though Trump’s doing terrible things in other places, I think that the environmental damage would’ve been done no matter what Republican president was in charge of things. This is the long-time wish list of the fossil fuel industry, and one after another they’re rolling back the quite modest regulations that tried in any way to rein them in.

A recent study by the Rhodium Group suggests that even without the Clean Power Plan, America’s emissions are expected to fall between 27 and 35 percent from 2005 levels by 2030. Isn’t the country moving away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy regardless of what happens in Washington?

McKibben: Yes, there’s no question of that. The economics of sun and wind are very hard to beat. The important question is how fast we’re doing it. Climate change is the first time-limited problem that we’ve ever come up against. If we don’t solve it quickly, we don’t solve it. And nothing that anyone’s planning solves it quickly enough to catch up with the physics.

As a professor at a small liberal arts college in Vermont, what do you see as the role of the academic, or more generally the role of the academy, in today’s climate movement?

McKibben: Let me generalize that question: What’s the role of everyone at the moment? We each have jobs where one could be making a difference nine-to-five on these most pressing problems of our age, but not enough of a difference. And so our biggest, most important work is our work as citizens. That’s what we have to get back to. That’s why we build movements, to allow people to be citizens in the fullest sense.

McKibben: Yes, there’s no question of that. The economics of sun and wind are very hard to beat. The important question is how fast we’re doing it. Climate change is the first time-limited problem that we’ve ever come up against. If we don’t solve it quickly, we don’t solve it. And nothing that anyone’s planning solves it quickly enough to catch up with the physics.

As a professor at a small liberal arts college in Vermont, what do you see as the role of the academic, or more generally the role of the academy, in today’s climate movement?

McKibben: Let me generalize that question: What’s the role of everyone at the moment? We each have jobs where one could be making a difference nine-to-five on these most pressing problems of our age, but not enough of a difference. And so our biggest, most important work is our work as citizens. That’s what we have to get back to. That’s why we build movements, to allow people to be citizens in the fullest sense.

Our biggest, most important work is our work as citizens. That's what we have to get back to.

You’ve built a really powerful movement, with tens of thousands of marches and events worldwide. And yet, during last year’s presidential debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, climate change was notably absent. Why has the movement struggled to make climate change a central issue on the campaign trail?

McKibben: This is a hard fight. And you’re right, we haven’t won it all. For me the best moment of all the debates came during the Democratic primary when Mr. Sanders quite forthrightly announced that climate change was the biggest problem the world faced, a new recognition for an American politician of that stature. And I take some comfort from the fact that he remains the most popular politician in the country.

I understand you met earlier today with some of the students from Fossil Free Yale.

McKibben: Yes, a bunch of students from F&ES.

What did you say to them?

McKibben: I said, thank you very much for keeping this work going. There are two pieces of good news: We’re winning across a wide variety of places. Six trillion dollars of endowments and portfolios have now been divested in whole or in part. This week, the welcome news came that 40 big Catholic institutions had divested, including Saint Francis’s own diocese of Assisi. The second thing I said to them is, this is one of those cases where it doesn’t matter completely whether you win or lose. The important thing is to keep the fight on so it’s in the face of the powerful people who are on Yale’s board and who administer the university. This is the perfect way to remind ourselves over and over again of the perfidy of the fossil fuel industry.

You recently wrote your first novel. Do you ever long to return to the Adirondacks, to lead a quiet existence and just write?

McKibben: Yes. I’m well outside my comfort zone. Like many writers, I’m essentially an introvert. It’s been hard work to jury rig myself into somewhat of an organizer. Happily, there are lots of other people who do this work, too.

What do you say to your neighbors in your own community to bring them on–board with the climate movement?

McKibben: I find climate change easy to talk about with rural Americans. For instance, on the road on which we live, in fact, all the roads in our county, the Public Works Department has spent the last five years systematically taking out all of the 8-inch culverts and putting in 10 and 12-inch culverts because the old book on how the world works doesn’t work anymore. We get much bigger rainstorms than we used to. People see that and they understand it and get what it means. In fact, our rural and quite-red county voted pretty heavily for Barack Obama, twice. Didn’t for Hillary, and there were all kinds of cultural things that made that hard. When she made her remarks about how ‘deplorable’ a lot of people were, I think everybody up and down my road heard it and said, ‘she’s talking about me.’ I campaigned hard for her across Ohio and Pennsylvania, and it was difficult.

How is the climate movement in the United States working to enhance its diversity?

McKibben: It strikes me that the movement is largely led by frontline communities and by indigenous communities. You saw it at Standing Rock last year. But long before that, there were indigenous groups out in front of all this. I think that’s been good. It’s natural for our work at 350.org because we work all over the world. Almost all the people who are leading the fight around the world are poor, and black, and brown, and Asian, and young because that’s what almost all the world consists of. And through our lens it seems the most obvious thing in the world.

What do you see as the next phase of climate activism in the U.S.?

McKibben: For the moment, there’s little chance that Washington will do anything useful. So one plays defense there and has to play offense everywhere else. The term of art at the moment is ‘sub-national actors’—states, cities, institutions. Everybody else now has to do a lot more than they’ve been doing in the past because it’s very clear that Washington’s not going to backstop them.

McKibben: This is a hard fight. And you’re right, we haven’t won it all. For me the best moment of all the debates came during the Democratic primary when Mr. Sanders quite forthrightly announced that climate change was the biggest problem the world faced, a new recognition for an American politician of that stature. And I take some comfort from the fact that he remains the most popular politician in the country.

I understand you met earlier today with some of the students from Fossil Free Yale.

McKibben: Yes, a bunch of students from F&ES.

What did you say to them?

McKibben: I said, thank you very much for keeping this work going. There are two pieces of good news: We’re winning across a wide variety of places. Six trillion dollars of endowments and portfolios have now been divested in whole or in part. This week, the welcome news came that 40 big Catholic institutions had divested, including Saint Francis’s own diocese of Assisi. The second thing I said to them is, this is one of those cases where it doesn’t matter completely whether you win or lose. The important thing is to keep the fight on so it’s in the face of the powerful people who are on Yale’s board and who administer the university. This is the perfect way to remind ourselves over and over again of the perfidy of the fossil fuel industry.

You recently wrote your first novel. Do you ever long to return to the Adirondacks, to lead a quiet existence and just write?

McKibben: Yes. I’m well outside my comfort zone. Like many writers, I’m essentially an introvert. It’s been hard work to jury rig myself into somewhat of an organizer. Happily, there are lots of other people who do this work, too.

What do you say to your neighbors in your own community to bring them on–board with the climate movement?

McKibben: I find climate change easy to talk about with rural Americans. For instance, on the road on which we live, in fact, all the roads in our county, the Public Works Department has spent the last five years systematically taking out all of the 8-inch culverts and putting in 10 and 12-inch culverts because the old book on how the world works doesn’t work anymore. We get much bigger rainstorms than we used to. People see that and they understand it and get what it means. In fact, our rural and quite-red county voted pretty heavily for Barack Obama, twice. Didn’t for Hillary, and there were all kinds of cultural things that made that hard. When she made her remarks about how ‘deplorable’ a lot of people were, I think everybody up and down my road heard it and said, ‘she’s talking about me.’ I campaigned hard for her across Ohio and Pennsylvania, and it was difficult.

How is the climate movement in the United States working to enhance its diversity?

McKibben: It strikes me that the movement is largely led by frontline communities and by indigenous communities. You saw it at Standing Rock last year. But long before that, there were indigenous groups out in front of all this. I think that’s been good. It’s natural for our work at 350.org because we work all over the world. Almost all the people who are leading the fight around the world are poor, and black, and brown, and Asian, and young because that’s what almost all the world consists of. And through our lens it seems the most obvious thing in the world.

What do you see as the next phase of climate activism in the U.S.?

McKibben: For the moment, there’s little chance that Washington will do anything useful. So one plays defense there and has to play offense everywhere else. The term of art at the moment is ‘sub-national actors’—states, cities, institutions. Everybody else now has to do a lot more than they’ve been doing in the past because it’s very clear that Washington’s not going to backstop them.

Published

October 12, 2017